Remorse, Regret, Release

Newly released from prison, Mordechai Samet relives the pain, guilt, and gratitude: “Don’t play games. Don’t get to where I did”

"I made a huge mistake,” Reb Mordechai Yitzchak Samet says without fanfare. “And I paid a horrible price.”

He is at home in Kiryas Joel, the chassidic enclave abutting Monroe, New York, following his early release from prison under the prison reform First Step Act that allows for home confinement from age 60. Yet thankful as he is for the shortened term, the toll of the last 18 years is evident on his careworn face. His beard is white, but the light has finally returned to his eyes after sitting behind bars for close to two decades, onceafter a federal court sentenced him to one of the harshest sentences for white-collar crimes — 27 years in prison.

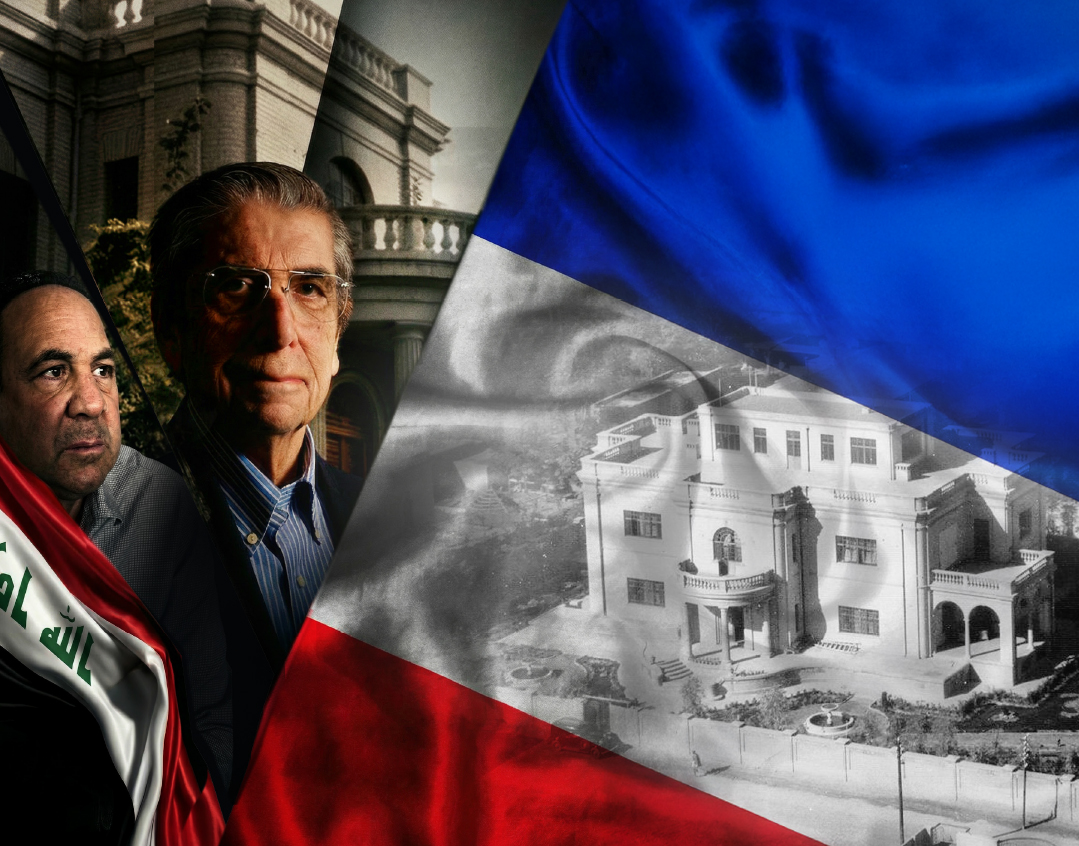

Mordechai Samet, arrested in an FBI roundup in 2001 and charged with running several fraud schemes, is ever grateful to the askanim who were able to secure his early release and have the immigration detainer on him lifted: Samet, an Israeli, is not an American citizen and faced deportation following his prison term, but the lobbying efforts paid off, as the father of 11 was able to return to his family upon his release.

He is full of praise and gratitude to HaKadosh Baruch Hu for finally reuniting him with his family, and he’s already taken advantage of his new lease on life to disseminate messages of emunah on one hand, and to warn the public against getting entangled with the law on the other.

“Don’t be tempted to get involved in anything that is illegal,” he tells Mishpacha in his first media interview since coming home. “It makes no difference how attractive it appears — it’s simply not worth it. You won’t get wealthy from it. Don’t be smart with the law. Don’t try to be an oiber-chacham. Don’t persuade yourself that the law is for others but not for you. It will only cause you endless suffering, not to mention the tremendous chillul Hashem. I hope that this message will resonate and will prevent others from experiencing the horrific years that I went through.”

Mordechai Yitzchak Samet is recovering slowly; he davens in a small shul near his home. In personal conversations, people try to get him to share some of the more harrowing stories from behind bars. In response, he emphasizes the middah of bitachon and hakaras hatov to Hashem. These two fundamentals gave him the strength to keep going during one of the longest incarcerations a chassidic Jew has ever experienced in an American prison for financial fraud.

But his is also a story of teshuvah, of rectifying the wrong in a way that will prevent others from falling into those same pitfalls that he did when he was younger and less cautious. Because, he says, the temptation to cut corners and to earn easy money is always waiting just around the bend. The yetzer hara whispers in a person’s ear about all kinds of different heterim and halachic leniencies that ultimately lead him to do terrible things.

Crackdown

The two-decades-long ordeal began one morning in March 2001, when FBI agents swept into Kiryas Joel, rounding up 14 suspects — chief among them Mordechai Yitzchak Samet — on suspicion of a string of financial crimes.

According to the indictment filed in a New York federal court, members of the group had falsified social security numbers and used the details to fraudulently obtain tax refunds, life insurance payments, and bank loans. In 2002, Samet was convicted on 33 counts of racketeering, money laundering, and fraud that netted about $5.5 million dollars.

The punishment was exceptional in its severity: 27 years in prison, in addition to fines and restitution of the sums. This meant that Samet, who was 42 years old at the time of his arrest, was not expected to see the light of day as a free man until he’d turn 69.

No one disputed the severity of his deeds or the justification for prison, but entities in the chareidi community bristled at the extremity of the sentence. Samet’s lawyers announced they would appeal the decision, but America is known to be very strict about federal financial crimes, and sentencing is often at the discretion of the judge overseeing the case. Hence, chances of sweetening the deal were very slim.

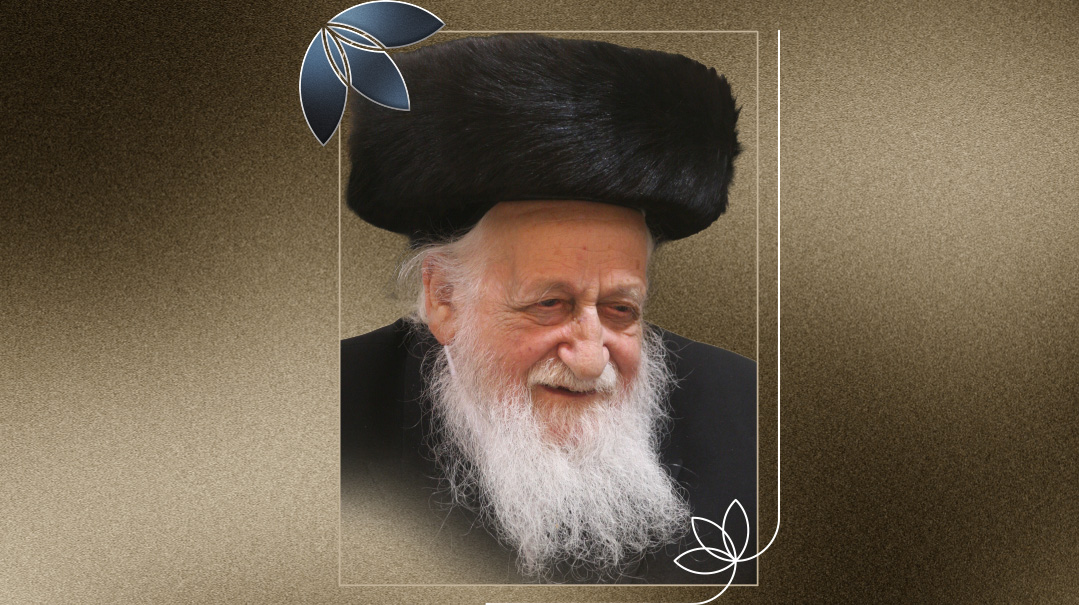

In light of the fact that Samet, a father of 11, had a large and young family, of children, rebbes, rabbanim, and askanim hadve gotten involved over the years to try to have his sentence commuted or reduced. Those involved didn’t question the fact that Samet deserved jail time, and they certainly didn’t present him as an innocent man — but they did feel the sentence was excessive for a white-collar crime. In June of 2015, a delegation of rebbes and roshei yeshivah visited the home of Israeli president Reuven Rivlin, pleading with him to exercise his influence on American authorities to commute Samet’s sentence on humanitarian grounds, and because he’d already sat for many years. The delegation included Ponevezh Rosh Yeshivah Rav Baruch Dov Povarsky, the Vizhnitzer Rebbe, the Rachmistrikva Rebbe and other rabbanim.

The efforts didn’t bear fruit, though — the prison gates remained locked, leaving no room for even a ray of optimism. But even so, Samet himself says he constantly held on to hope. When it became clear to him that salvation was not dependent on some stroke of lawyerly genius or leadership benevolence, he knew he could only rely on One Source.

Samet spent most of his term in Otisville, a facility preferred by religious prisoners because of its proximity to New York and its relatively decent conditions. At the peak, there were dozens of chareidi inmates at Otisville, which helped combat some of the solitude and feelings of disconnect.

“The hardest minutes in prison are getting up in the morning, when you realize that you’re headed for another day behind bars,” he describes. “I prepared myself a sign with the words Modeh Ani, which I hung across from my bed. It was my lifesaver each morning when I got up. I tried to strengthen myself during those minutes and to start my day with emunah and bitachon.”

Our Shame

“I cannot bear to think of the pain I’m causing my family — my wife, my elderly parents, my children,” Reb Mordecahi Yitzchak told Mishpacha in an anonymous interview from prison several years ago, after nearly 15 years behind bars. “The trauma, the grief, the shame, the stigma. How can I ever deal with the guilt of knowing that I brought this upon my family? It’s difficult to bear, and watching my loved ones suffer must be one of the greatest atonements.”

His greatest heartache, and his greatest blessing, was his wife.

“I don’t want to keep you chained to a prisoner with a 27-year sentence,” he told her, offering her a divorce so that she wouldn’t remain an agunah for close to three decades. “I’m your husband, and I care about you. Today, as a prisoner, this is how I show you that I care.”

But, according to Reb Mordechai Yitzchak, she didn’t say, “How many times did I beg you not to do what you did?” She didn’t say, “Why didn’t you listen to me and change your ways when you still had a choice?” She didn’t say, “You made your own bed, now lie in it.” Instead she said, “This is our test, I will not leave you. Hashem will help us through it.”

“I wouldn’t have survived without her,” he admitted. “I only hope HaKadosh Baruch Hu will repay her in ways that I never can.”

Even from his prison cell, long before he was released, Reb Mordechai Yitzchak shared the lessons he learned behind bars with others — with whomever he could reach. “I caution them to remain on the path of the straight and narrow, I show them a living example of what happens to those who don’t,” he said. “I go into horrific, graphic detail of what those caught on the wrong side of the law endure. The day I was arrested was the day the sun set on my life. I was exposed, my family was exposed, my community was exposed — we’re all exposed beneath the magnifying glass of sensation-seeking journalists…. Before I fully knew how utterly humiliating and taxing and frustrating a trial is, before I knew how despicably inhumane life in prison is, before I knew that I’d be sentenced for close to three decades, I already rued the day I got involved in bending the law to suit my needs — my wants.”

Because of his extreme sentence, some inmates assumed he was a shrewd operator who’d made a financial killing on the outside, and would be a good candidate for black-market business on the inside. But Samet was loath to get on the opposite side of the law again.

“I never aspired to be rich,” he said then, in his prison interview. “All I wanted to do was scrape by, pay tuition, mortgage, kehillah dues, and make bar mitzvahs and weddings without needing to accept charity. Yes, I know my reasoning was faulty, how well I know that today. And every last cent I have unlawfully earned has long been restituted to the rightful parties. Today I’m as destitute as a man in prison can be and my family lives off the largesse of the community.”

During the prison years, Reb Mordechai Yitzchak’s young family grew up. They saw their father only during short visits to the prison, or during the rare occasions when the authorities let him out to attend the wedding of a child. How did they keep their heads up in the face of it all?

Perhaps it’s because their father had his own secret weapon that kept him going the whole time. “That’s the power of emunah. I treated each day as if it was my last one in prison,” he shares. “There is a story about a rebbe who saw a boy being accosted in the forest and then beaten badly. He was surprised that the child didn’t raise his voice in a cry, and instead suffered silently. When the boy was asked how he got through it, he replied, ‘With each blow, I thought it must be the last one….’

“When a Yid knows that the One hitting him is his Father, Who wants only the best for him, he also knows there is an end to everything. I hoped every day that today would be the last day. My emunah was so strong that every time the phone rang I was sure they were coming to tell me, ‘Samet, you’re going free!’ ”

What were the hardest moments? The family milestones he missed? The simchahs marking the next stage in life he couldn’t attend? “I can’t really point to a specific moment,” he says, “because after they pass, you forget everything. But there wasn’t a minute from when I was imprisoned until now when I had any questions or doubts to Hashem. I knew that I deserved it, Hashem does everything, and nothing bad comes from Him. When you live with this emunah, you realize that when the moment comes, HaKadosh Baruch Hu releases prisoners, and that He would take me out of the darkness as well.

“One of the main things that kept me going was the knowledge that I was fulfilling the mission that Hashem sent me on. For some reason, I needed to be there. I kept visualizing a person working for the Mossad as an undercover agent in an Arab country. No one knows what he’s doing or who he really is, but he knows he’s serving a purpose. That’s sort of how I felt — carrying out a mission as a soldier of HaKadosh Baruch Hu even in the darkest place.

“I would tell myself over and over again: This is what Hashem willed and here He will care for me, just as He cared for me when I was a free man. And so I laid down some ‘house rules,’ the rules of my new ‘home.’ The good choices I had made before my incarceration, the mitzvos and minhagim and legacies that are mine will endure, even if I’m here because of gross error and sin. That doesn’t mean I should give up and relax my standards in Yiddishkeit. To the contrary — I must strengthen myself so that I grow in my avodas Hashem. I can’t afford to slide in Yiddishkeit. That’s the most important thing — really the only thing — I have now.

“Taking a hard look at my roots, at the derech with which my parents gifted me, ignited the desire to perpetuate my mesorah, and I felt compelled to hang on to it with all my might.”

And so, Samet made several nonnegotiable rules for himself. Rule number one: Regarding TV movies and magazines he’d never view or read as a free man, he wouldn’t in prison either, even if it’s the primary distraction all the other inmates turn to. “I’d review mishnayos in my head, I’d read outdated Jewish newspapers, I’d count the floor tiles — but I would not watch. Nothing would make me watch that schmutz.”

First Steps

One of Samet’s most shattering moments was after the failed bid for a presidential pardon, involving the efforts of rabbanim in America and Eretz Yisrael. At that point, Samet felt that all chances of release before the entire sentence was served had been dashed. And so he did what he’d been doing all along — he buried his pain and grief in his Tehillim and in strengthening his emunah.

“I kept repeating to myself that the yeshuah of Hashem comes in the blink of an eye, even in a situation that seems totally hopeless,” he relates. “When a Yid has difficult problems, he must remind himself that ‘Hu Levado asah v’oseh veya’aseh lechol hama’asim’ — only HaKadosh Baruch Hu, the One Who orchestrates every single thing, could help and save me.”

It was at that point, when despair threatened to crush his heart and push him over the edge into a severe depression, that the turnabout that no one foresaw occurred. The one largely responsible is askan and baal chesed Rabbi Moshe Margaretten, the linchpin of the Tzedek Association, which has been a key lobbyist for prison reform.

As someone who has taken the plight of chareidi prisoners to heart, Rabbi Margaretten hoped that perhaps a new way could be found to breach the prison walls for so many who had already paid their dues.

“Legal experts agree that the sentencing system in the country is often draconian and needs reform,” Margaretten tells Mishpacha. “There are aid organizations and human rights groups on both the right and left that have been advancing various reform plans, but those plans are often entangled with political agendas that ignite vehement opposition from the opposing side. We knew that in order to advance a reform that would prevail over all the political pitfalls, we would have to get bipartisan support, and to do that we needed to work without any underlying ideologies.”

Rabbi Margaretten and members of Tzedek Association were instrumental in helping advance the First Step legislation through congress and get it signed by President Trump in December of 2018. (In fact, due to his extensive involvement in the sentencing reform legislation, Margaretten received an invitation from the president to light the candles at the White House Chanukah ceremony.)

The First Step early release program meant, among other clauses, that inmates who are serving time in federal prison for similar types of crimes are eligible for the Elderly Home Confinement Program, which would allow for early release to home detention when they turn 60 years old and have served at least two-thirds of their term. This would allow them to remain with their families in their own communities, enabling them to attend shul and interact with their relatives and friends. But with Samet — who would be turning 60 this past September — they hit an obstacle that threatened to thwart the whole effort. Because Samet does not have American citizenship, there would be an immediate deportation order issued for him upon his release.

Rabbi Margaretten didn’t give up though, and worked to find a way that Mordechai Samet would be allowed to head home at last. Having served nearly 18 years in federal prison, it was a top priority of many askanim to have his sentence shortened as others have been.

“This was a very complicated legal situation,” Margaretten says. “As far as the dry law goes, Samet was eligible for early release. yet. But the prison authorities claimed that as long as his status was not resolved, they had nowhere to release him to.”

But still, Margaretten and his team of askanim didn’t give up. Last year, Samet went to the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), the court system for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), asking for his detainer to be removed. The EOIR ruled against him though, and two additional appeals were denied as well. At that point, Rabbi Margaretten and Tzedek Association knew the only open avenue would be a grant of clemency by the president. And to that end, they secured a request from eight members of the House of Representatives, insisting that Morechai Samet was suffering from the technicality of the immigration detainer and not by any legal requirement. Another point in his favor was that there was no restitution requirement, as all injured parties were paid in full, and had signed a letter requesting leniency in his case.

They also hired the services of John Sandweg, who had served as the acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement in the Obama administration, to exercise his connections with the immigration authorities to issue an injunction on the deportation order against Samet.

“This step was far from an assured success, because under the Trump administration the whole issue of immigration became an explosive political hot potato, and the immigration laws have been tightened significantly,” Margaretten explains.

Still, Sandweg advised them to request a Stay of Removal, which would lift the detainer for one year, although in recent years, a Stay of Removal is difficult to receive due to the heightened enforcement of immigration policy under the current administration. Tzedek Association used their relationships with several politicians, and with their help, the assistance of Rabbi Zvi Boyarsky and the Aleph Institute, attorney Mr. Gary Apfel, and White House support, the detainer was removed earlier this year.

“For months, the issue was tossed back and forth,” says Rabbi Margaretten. “But when the pandemic broke out and some of the Orthodox prisoners were sent home, Samet remained in prison, in mounting isolation, because no legal solution to his status had been found. Then, a breakthrough occurred when the official in charge of the detainer removal was convinced of the unusual nature of the situation and approved the release.”

For Samet, the news of his release was a grateful surprise. He’d already resigned himself to another seven years, when the warden came in urging him to gather his things to get in the van waiting outside.

“HaKadosh Baruch Hu orchestrated the circumstances and sent His good emissaries,” Samet says. “It was beyond wondrous — for 20 years, dozens of people had worked for me and invested a fortune of money. Of course, I have tremendous hakaras hatov to all the wonderful people who helped me throughout — from President Donald Trump, who got involved, to all those who davened, and took on kabbalos on my behalf, and exercised their contacts and did what they could. It’s important for me to stress that there are still Jewish prisoners incarcerated, like the bochur both Sholom Rubashkin and I became close to, Michoel Yosef (Shawn)Shalom ben Leah, and others, who we need to daven for. I know how hard it is for him, and the thought that I left him there gives me no peace.”

He also has tremendous gratitude to all the people who helped him over the years. “Every tefillah said for me, it all brought the yeshuah closer even if we didn’t see immediate results. I drew strengths from the letters that children sent me writing that they had pledged not to speak during davening for 40 days. We have to know that everything helps, even if we, with our limited vision, can’t see the results. When the right moment comes, the yeshuah happens.”

In retrospect, Samet admits that if he’d had the wellsprings of bitachon and emunah that he developed and built up during his long years in prison, he would never have gotten into the whole dangerous and dubious enterprise that entangled him so badly.

“Anyone who has strong emunah knows that HaKadosh Baruch Hu provides parnassah to all — from the tiniest creations to the largest ones — without a person needing to employ questionable methods, and especially when those actions are against the law,” Samet says today. “No tricks. And it’s not only because I sat in prison for nearly two decades, but because HaKadosh Baruch Hu says not to do these things. And our job is to make a kiddush Hashem in This World and not, chalilah, the opposite.

“Ultimately, we don’t gain anything and we pay a heavy price. I suffered so much, I caused so much heartache and pain to myself and others. I ask my children forgiveness because they had to suffer so much because of my lack of caution. I ask mechilah from my wife, a tzadeikes, who waited for me all these years. Today, I hope and pray that my sins have been atoned for, and that, as Hashem promises, my transgressions have turned to merits. But please, no one should take the path I did to get there.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 834)

Oops! We could not locate your form.